THE PIOUS PERSON: THE MORAL THEORY OF ROGER SCRUTON

Good Sir Roger

Sir Roger Scruton was undoubtedly the most brilliant conservative mind of the last one hundred years. I feel towards him as Beethoven felt towards Handel, “He was the greatest, I would cover my head and kneel at his tomb.”

The most articulate voice of Anglo-Saxon conservatism since Edmund Burke, Sir Roger passed away almost three years ago, at the age of 74.

It’s difficult to recommend where to begin with Scruton, he wrote more than 40 books ranging from ethics, to aesthetics, to wine, to sex, to politics, and to metaphysics. As a public intellectual, he also left behind a legacy of videos. If I had to pick, I would say that a good book to start with would be How to Be a Conservative, and a good video would be Why Beauty Matters.

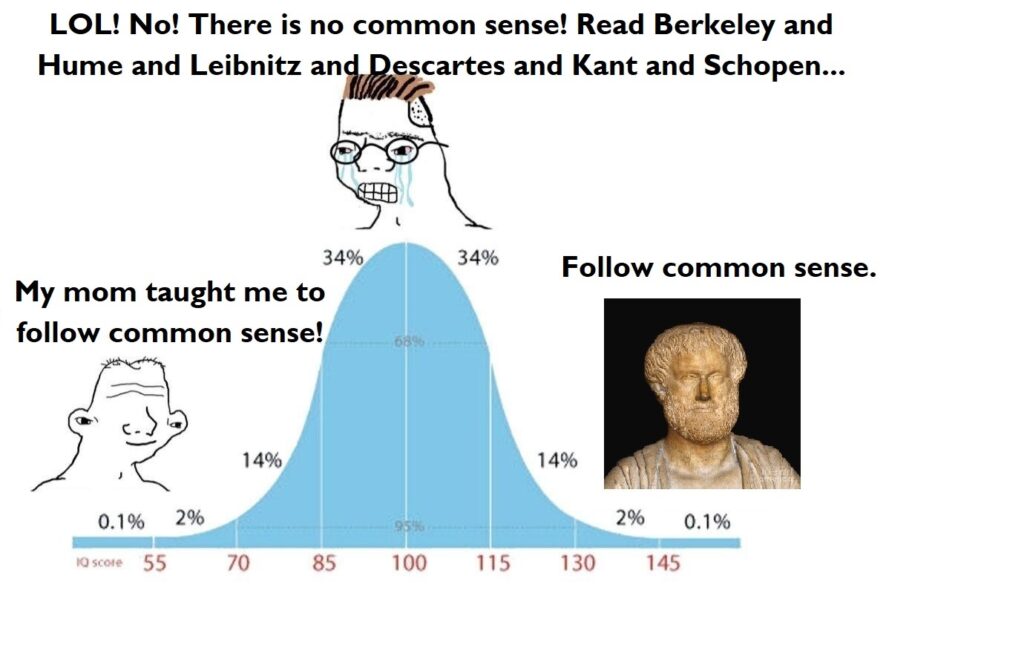

Placing Scruton the philosopher within a philosophical tradition is not an obvious task. He was trained as an analytical philosopher in the Cambridge tradition but had quickly realized the limitations of that school in saying anything meaningful about the things that really matter. He draws inspiration from Hegel but rejects Hegel’s convoluted metaphysics. He makes use of some of Kant’s ideas but has no interest in rationalistic absolutes.

To me, like all good philosophers, Scruton is ultimately an Aristotelian. And he does what Aristotelians of every age do: He clears away the gunk of his time and makes way for common sense.

The Elements of Morality

Scruton naturally wrote quite a bit about morality, including a few complex books: Sexual Desire, Modern Culture, The Soul of the World, and On Human Nature. Unexpectedly, however, the place where he summarizes his moral thinking most effectively is in his book about animals: Animal Rights and Wrongs.

It’s a short book dedicated (among others) to the pig “Herbie, who has just been eaten.” To identify the proper place for a moral feeling towards animals, Scruton must first lay the foundation for moral feeling in general, which results in a magnificently lucid theory of human morals.

Moral sentiment and reasoning flow in Scruton’s theory through a stack of basic components: The Moral Law, Virtue, Sympathy, and Piety.

The Moral Law

Scruton’s piece of fundamental metaphysics is the idea of the person. Influenced by Buber, Scruton sees all moral human interaction as an aspect of the “I-Thou” experience. I see you as a person, and you see me as one. I see myself in you and you see yourself in me. We recognize each other as persons, and thus we immediately attribute to one another the characteristics of persons: motivation, intent, judgment, and sense.

Scruton also sees us as communal beings. In a debt to Hegel, he recognizes that we become ourselves through others. Meaning, our life in a community and our interaction with others are the things that bring about the moral sentiment; not an abstract “natural state” or a model of a desert island.

And so, recognizing himself and his neighbors as persons, Scruton affirms Kant’s moral law or his Categorical Imperative: We should never treat others as a means to an end. Only as persons.

This is the source of the idea of rights. To avoid treating you as an object or a means to my end, it is my duty to acknowledge your rights. I must recognize a shield of rights around you, as I demand you to recognize such a shield around me. “The moral law forbids us to override the rights of others and holds us to our duties.”

As an aside, This is also the basis for the idea of “Natural Law.” But Scruton warns us (as Aristotle does in his Ethics, saying that a discipline can only be as precise as its nature allows), that the Moral Law provides a procedure, not a full list of rules. It doesn’t tell us what our rights and duties are. But it does provide a process – once our rights are established (say, by the tradition of the common law, or by the folkways of the English-speaking peoples) we should settle our disputes according to a calculus of rights and duties.

Virtue

Acknowledging the Moral Law does not necessarily mean acting upon it. What should compel me to treat you as a person if my appetite lures me to do otherwise? What if I desire your house, your wife, your car?

And so the ancient idea of virtue is established. An honorable man would cultivate the tendency of acting morally. An honorable society would cultivate honorable men. Scruton upholds the cardinal virtues of classical times – courage, wisdom, justice, and temperance.

A courageous man would uphold moral judgment even against the sentiments of others. A wise man would follow the best examples known to experience and apply rational considerations. A just man would approach morality impartially. A temperate man would find a way to settle extremes and contradictions.

To the ancient virtues, Scruton adjoins the Christian virtue of charity and the pagan virtue of loyalty, as explained below.

Sympathy

Scruton observes that a calculus of rights and duties, and a dispensation to act accordingly, do not provide a complete picture of the moral being. We are also motivated by sympathy, which gives birth to the more flexible virtue of charity.

Charity for Scruton is the “disposition to put yourself in another’s shoes and be motivated on his behalf.” It is a rational motive that should be encouraged by the moral community. Without charity, the community loses a major source of strength, needed for its survival – “the pleasure of giving and receiving in reciprocal concern.”

In defiance of Nietzsche’s view that charity and pity represent a kind of contemptuous worship of weakness, Scruton sees charity as the twin of joy. My ability to put myself in your shoes allows me indeed to pity you, but also to rejoice in your success and know that you will rejoice in mine. Scrutonian charity is the font of brotherly feeling, so needed by communities in order to survive.

Yet sympathy, being flexible, should be balanced by the other virtues as well as by the moral law. It may lead to a ridiculous form of utilitarianism in attempts to spread joy to the greatest number. For instance, my sympathies for the hungry family next door could lead me to deprive my wife of her food and dispense it instead to that hungry family. But I would be violating my duties to my wife that way, and so the cardinal virtues and the moral law should govern the application of sympathy.

Piety

The final building block driving our moral feeling and consideration is piety. Scruton defines it as the Romans would, as a solemn devotion to what is sacred and transcendent. Piety, according to Scruton is “rational, but not amenable to reason.” Meaning, conserving a layer of inviolable deep-seated convictions (such as the taboo on incest) is a rational thing. The opposite would be to constantly open and re-open the sacred, transcendent, and timeless to the shifting fashions of the ever-changing times. Yet even though it is rational, piety cannot be rationalized. Once pieties are attempted to be justified by reason (“Cannibalism is bad because human flesh is unhealthy!”) they stop being pieties.

Moral Conflict

Moral dilemmas are natural for mortal, passionate creatures. Were we immortal and inviolable, we could easily abide by the Moral Law without conflict or doubt. But we are mortal and passionate, Scruton observes. We are not marbled idols standing serenely on a Holy Hill, but creatures motivated by sympathy and fellow-feeling. And so conflicts arise.

In such cases, the Moral Law should take precedence. We should perform a calculus of rights and duties. But rights and duties can conflict. I may owe both John and Jane money, but have enough to only pay one.

And so virtue kicks in. I may like Jane more than John, but giving her preference would be unjust. Perhaps I should follow the temperate and courageous path, be open with them both, and attempt to reach a compromise.

Virtue though may also at times be exhausted. Yes, I owe both John and Jane money, but a compromise is impossible. I may choose then to follow a just sympathy and perhaps even a utilitarian calculation – John has a large family, so by paying him first I may increase the well-being of more people.

But piety speaks as well. John and Jane may need my money, but my children need it too. Piety, my unspoken vows to my family, demands that I address their needs first.

The result is a morality that while being Aristotelian in nature, also confronts the overly punctilious moral theories of the likes of Descartes and Rawls, and simultaneously the wilder poetry of the likes of Nietzsche.

If it sounds like the common sense of your grandmother, your sentiment is correct. For that is the end of all great philosophy.

Follow us on Twitter!

And sign up for updates here!